On a knife’s edge

by LEVI STAHL, neocartography by DIANA KOLSKY

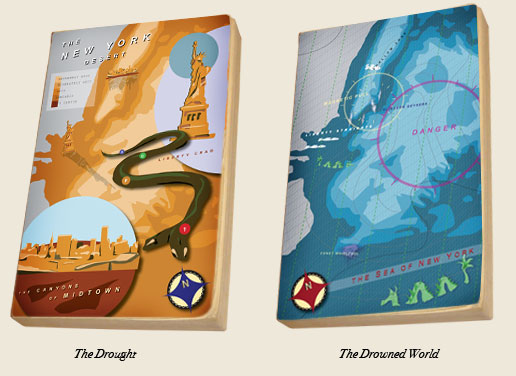

Burning World and Drowned World

Burning World and Drowned World

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I've tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice

I think I know enough of hate

To know that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

—Robert Frost, “Fire and Ice” (1920)

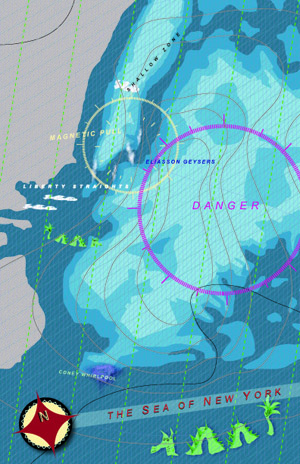

In 1962 J. G. Ballard destroyed our world with water. Two years later, he destroyed it with drought. For Ballard, the method was far less important than the resulting landscape; what we make of it far less important than what it makes of us. As Martin Amis has written, Ballard's strength is “the ability to invest abstract vistas with intense and furtive life.” In The Drowned World, our cities have become swampy Jurassic lagoons; in The Drought, our oceans are the last source of water, and small bands of humans rely on decrepit desalination technology to eke out just enough potable water, transforming beaches into miles of parched salt dunes.

Though Ballard depicts collapsed societies, he mostly passes over the details of their fall in favor of chronicling the unexpected transformations these damaged landscapes wreak in the survivors. Under the blazing heat and oppressive humidity of The Drowned World, torpidity reigns. Needs begin to seem needless, desires undesirable, and time slows to a crawl. Dreams — powerful, distracting, all-encompassing dark dreams — begin to fill sleep, and sleep itself becomes a siren ... calling ... calling. As a scientist in the novel explains:

The innate releasing mechanisms laid down in your cytoplasm millions of years ago have been awakened, the expanding sun and the rising temperature are driving you back down the spinal levels into the drowned seas submerged beneath the lowest layers of your unconscious, into the entirely new zone of the neuronic psyche. This is the lumbar transfer, total biopsychic recall. We really remember these swamps and lagoons.

Set against the lure of slipping into a thoughtless, changeless deep time, what attraction could the responsibilities of science and survival hold?

In the forbidding aridity of The Drought, on the other hand, all thought turns to eking out an existence, and even the loners and the self-sufficient find themselves drawn to those who seem to have answers, or power, or both. People band into armed camps around charismatic religious leaders; at the same time, those who were unfortunate enough to be misfits in the old society — the mentally ill, the disabled, even the plain old eccentric — flourish. These people, Ballard seems to suggest, have always been forced to view the world as a hostile environment. Suddenly they are not alone in that situation, and in an odd way they’re better prepared to deal with it than those whose lives had heretofore been easy.

We are, Ballard reminds us, perpetually living on a knife edge — or, perhaps more apt, on the banks of a fickle river. Sand and water may be antitheses, but it is the latter that defines both; its absence is what makes a desert. Alter our relationship to water, and the form of our cities and our society — and, Ballard posits, our very minds — is revealed for what it is: merely one option among many. The next time I wander the dry canyons of Manhattan, I’ll think of rising water and mountains of salt, parched throats and deep time, and be glad this is the reality we've ended up with — so far.

“When you cross those steep bridges into the weird swarming life outside the center of things, and see the template of this city from its approaches, you confront the monumentality of ancient Rome, you become tiny and incidental in the realm of geological time. It takes thousands of faceless beings to build those massive walls and string girders miles above the earth. Thousands of faceless faces, eons of forgotten time, a dark river pulling everything under. Every man for himself and God against all, tojours c’est vrai, c’est tout.” — from Do Everything in the Dark (2003), by Gary Indiana

The Drowned World (1962)

The Drought (1965, first published in shorter form as The Burning World in 1964)

by J. G. Ballard